On the 19th of November a United Express commuter flight landing in Quincy, Illinois collided at an intersection with a private Beechcraft King Air, sending the two planes sliding off the runway in flames. As witnesses rushed to help, they found that the 12 passengers and crew of United Express flight 5925 had all survived the crash — but the door wouldn’t open, trapping them in the burning plane. After their frantic efforts to open the door failed, fire ripped through the cabin, killing everyone inside. The National Transportation Safety Board investigation had to answer two key questions: which crew was at fault, and why did no one survive the crash? The investigators’ conclusions contained sobering lessons about vigilance, right of way, and the value of listening to in-flight safety briefings.

For its services to small, regional airports, United Airlines has long employed smaller contract airlines which operate under United Express branding. One of these was Great Lakes Airlines, a large regional airline which operated small airplanes on behalf of several name-brand carriers, including United. With a fleet of 19-passenger Beechcraft 1900C twin turboprops, Great Lakes/United Express flew passengers into a wide variety of midsized towns across the central United States.

Among these destinations was Quincy, Illinois, a town of about 40,000 people on the banks of the Mississippi River. Quincy Regional Airport is the main air travel hub for the community. Historically, the airport was never served by more than two carriers at a time; in the 1990s, these were Trans World Express and United Express, both of which operated daily flights to and from Chicago using the Beech 1900C. Due to the low volume of commercial traffic (never more than two takeoffs and landings per day) Quincy Regional Airport did not and still does not have a control tower to coordinate traffic on its three intersecting runways and in the surrounding airspace.

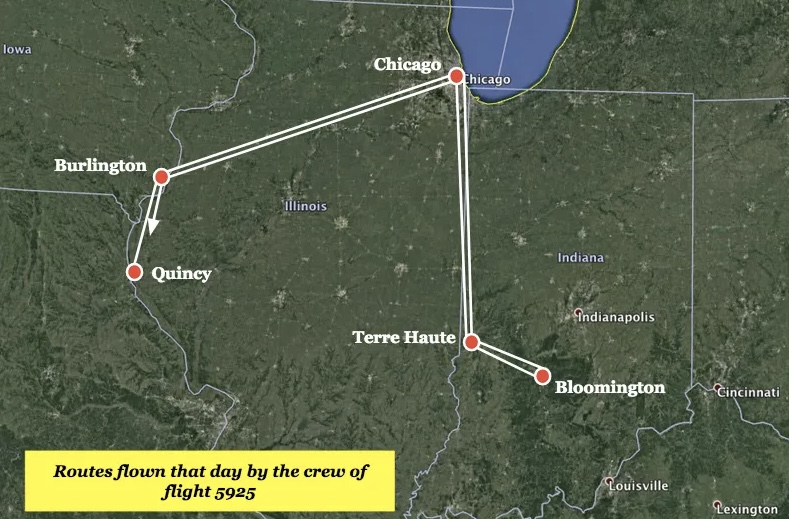

The 19th of November was a day like any other for 30-year-old Captain Kate Gathje and 24-year-old First Officer Darren McCombs, the two Great Lakes pilots who would be flying the service to Quincy that day. After leaving Quincy early that morning, they had spent the day hopping between several Midwestern airports, before finally making their way back to Quincy after stops in Chicago and Burlington, Iowa. The Burlington-Quincy leg was to be their eighth and final flight of the day, and they were over two and a half hours behind schedule due to a mechanical problem — pushing their working day over into the hours of twilight.

Meanwhile at Quincy Airport, retired TWA pilot turned flight instructor Neil Reinwald was preparing to fly home with one of his students, Laura Brooks. Brooks was a commercial multi-engine rated pilot who was trying to build up enough hours to get a job at a regional airline; in order to help her accrue flying time, Reinwald brought her along on many flights on an informal basis. Today he and Brooks had been flying a twin-engine, seven-passenger Beechcraft King Air A90 back and forth between Quincy and Tulsa, Oklahoma to introduce the plane to potential buyers. This was Brooks’ first time in a King Air, and Reinwald was also taking the opportunity to teach her some of the basics of flying this type of airplane.

Shortly before 5:00 p.m., as dusk enveloped the region, United Express flight 5925 began its approach to Quincy Airport with ten passengers and two crew on board. First Officer Darren McCombs was flying the plane while Captain Kate Gathje handled the radio. Because Quincy Airport was an “uncontrolled airport” — an airport without a control tower — it was her responsibility to announce their every move over a common frequency, so that all airplanes operating in and around Quincy would know their intentions.

At 4:55, Laura Brooks, the student pilot on the private King Air, called on the common frequency and said, “Quincy traffic, King Air one one two seven delta’s taxiing out uh, takeoff on runway four, Quincy.” Brooks had a pronounced lisp which made her voice rather distinctive.

On board the United Express Beech 1900, the pilots joked about her voice. “Quincy twaffic,” Captain Gathje said with a chuckle.

“Sounds like a little kid,” agreed First Officer McCombs.

Moments later, a private single-engine Piper Cherokee also called on the common frequency. “Quincy traffic, Cherokee seven six four six Juliet back-taxi uh, taxing to runway four, Quincy,” said the pilot.

“They’re both using four,” said Gathje. Runway four intersected runway 13, their planned landing runway, so they would need to coordinate their takeoffs and landings. As the landing plane, flight 5925 had the right of way, but Gathje would need to make sure the other pilots were aware of that. At 4:57, she announced, “Quincy area traffic, Lakes Air 251 is a Beech airliner currently 10 miles to the north of the field. We’ll be inbound to enter on a left base for runway one three at Quincy. Any other traffic, please advise.” There was no reply. (Note that while the flight was marketed as United Express 5925, it was using the callsign Lakes Air 251.)

At 4:59, Laura Brooks came on the radio again. “Quincy traffic, King Air one one two seven delta holding short runway four. Be, uh, takin’ the runway for departure and heading, uh, southeast, Quincy.”

Coming in hot toward runway 13, Gathje was paying attention to Brooks’ comments. “She’s taking runway four right now?” she asked to First Officer McCombs.

“Yeah,” said McCombs.

Keying her mic again, Gathje said, “Quincy area traffic, Lakes Air two fifty one is a Beech airliner currently uh, just about to turn, about a six mile final for runway one three, more like a five mile final for runway one three at Quincy.”

At that moment, the King Air was holding at the threshold of runway four with the Piper Cherokee in line behind it. Having received no response to any of her transmissions, Captain Gathje again asked, “The aircraft gonna hold in position on runway four, or you guys gonna take off?”

After several seconds with no reply from the King Air, the pilot of the Cherokee piped up instead. “Seven six four six Juliet, holding for departure on runway four, (behind) on the uh, King Air.”

At that exact moment, the ground proximity warning system on the Beech 1900 called out “TWO HUNDRED” to inform the pilots that they were 200 feet above the ground. As a result, Gathje and McCombs heard, “Seven six four six Juliet, holding for departure on runway four, TWO HUNDRED on the uh, King Air.” Although voice of the Cherokee pilot was male and the voice of the King Air pilot was female, Gathje apparently missed this difference. Because the Cherokee pilot replied to her question, which was aimed at the first plane in line to take off, and because he used the word “King Air,” she made a snap assumption that the transmission came from the King Air.

“Okay, we’ll get through your intersection in just a second sir, we appreciate that,” she said.

But in fact, there was no indication that the King Air pilots ever heard that the Beech 1900 was about to land. Nine seconds after Gathje’s last transmission, instructor pilot Neil Reinwald pushed the throttles forward for takeoff, and the King Air began to rumble off down the runway.

Each plane should have been at least partially visible to the pilots of the other, but with the United Express pilots occupied with their final preparations for landing and the King Air pilots apparently unaware of the Beech 1900, neither managed to spot the other converging on the twilit intersection.

At 5:00 and 59 seconds, flight 5925 touched down on runway 13, and Captain Gathje called for max reverse thrust. But a split second later, she caught sight of the King Air hurtling toward them on the intersecting runway. “Oh shit!” she exclaimed, slamming on the brakes.

“What? Ooooh shit!” said McCombs.

On the King Air, Reinwald and Brooks apparently spotted the Beech 1900 just seconds away, prompting them to slam on the brakes as well. They steered to the right to try to avoid the airliner, while United Express pilots Gathje and McCombs steered hard to the left, but it was too late. The King Air plowed directly into the side of the Beech 1900, severing both planes’ fuel tanks and triggering a raging fire. Tangled together by their wings and engines, the two planes skidded to a halt on the edge of the intersection, surrounded by flames.

The impact forces involved were not much more than a moderate car crash, and everyone survived the collision with minimal injuries — but their ordeal was only just beginning. The King Air came to rest in the pool of spilled fuel and was overrun by flames within seconds. Reinwald and Brooks managed to get up out of their seats in an attempt to reach the rear exit, but they were quickly overcome by noxious fumes and collapsed from smoke inhalation. On board the Beech 1900, flames had not yet penetrated the cabin, and the passengers rushed toward the main exit door, on the forward left part of the aircraft. While Captain Gathje shut down the engines, First Officer McCombs went back to open the door, but to his horror, it refused to budge. The crash had deformed the doorframe, causing the door to jam!

Meanwhile, a pilot who was in a nearby hangar rushed to the crash site after hearing an explosion. He arrived to find smoke already filling the cabin of the Beech 1900, but he could see and hear people moving about inside. As he approached, Captain Gathje stuck her head out the cockpit window and pleaded with him to “get that door open.” He rushed to the door and pulled on the handle, but no matter what he did, it would not open. He could feel someone wiggling the handle from the inside; people were alive behind that door, and he needed to save them. Moments later, the United Express pilot who was scheduled to fly the Beech 1900 on its next leg also arrived at the scene. Desperate to save his coworker and her passengers, he tried to open the door, but he too was unsuccessful. Beaten back by the heat of the flames, they were forced to abandon their efforts. Less than a minute later, an explosion tore through the night, and they looked back to see the plane totally consumed in flames. There was no more sign of Kate Gathje at the window — it was obvious that she and all her passengers were already dead.

In those last moments aboard the plane, First Officer McCombs apparently abandoned his attempts to open the forward door and began moving back to try the left overwing exit instead. Unfortunately, he never made it. As black smoke filled the cabin, he and Captain Gathje, along with all ten of their passengers, perished from the toxic fumes.

Desperate to save his coworker and her passengers, he tried to open the door, but he too was unsuccessful. Beaten back by the heat of the flames, they were forced to abandon their efforts. Less than a minute later, an explosion tore through the night, and they looked back to see the plane totally consumed in flames. There was no more sign of Kate Gathje at the window — it was obvious that she and all her passengers were already dead.

In those last moments aboard the plane, First Officer McCombs apparently abandoned his attempts to open the forward door and began moving back to try the left overwing exit instead. Unfortunately, he never made it. As black smoke filled the cabin, he and Captain Gathje, along with all ten of their passengers, perished from the toxic fumes.